Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'Piano Bar - Keys don't fit', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'High Noon', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm

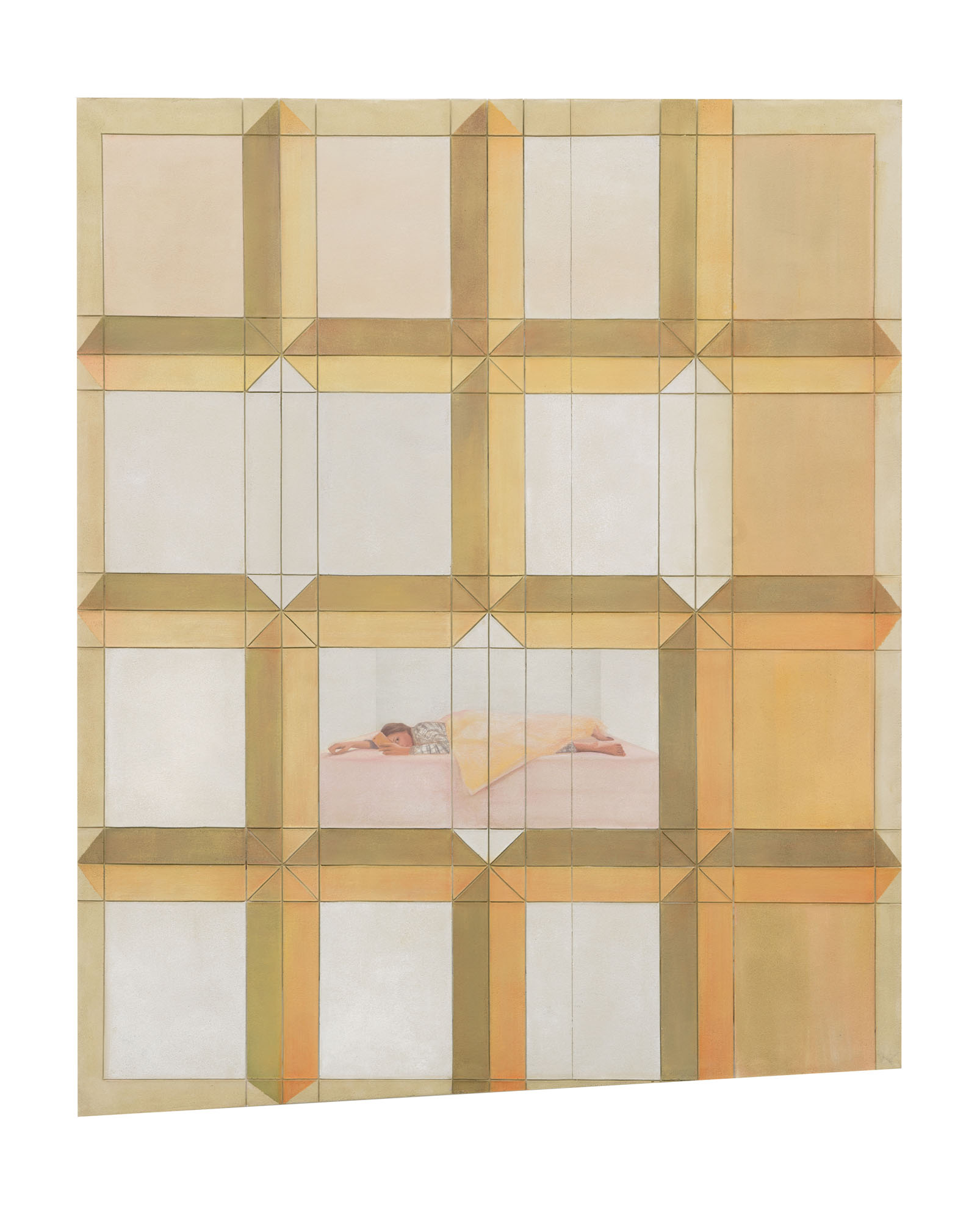

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'Interlude with Sunrise', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'Interlude with Sunrise', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm (Detail)

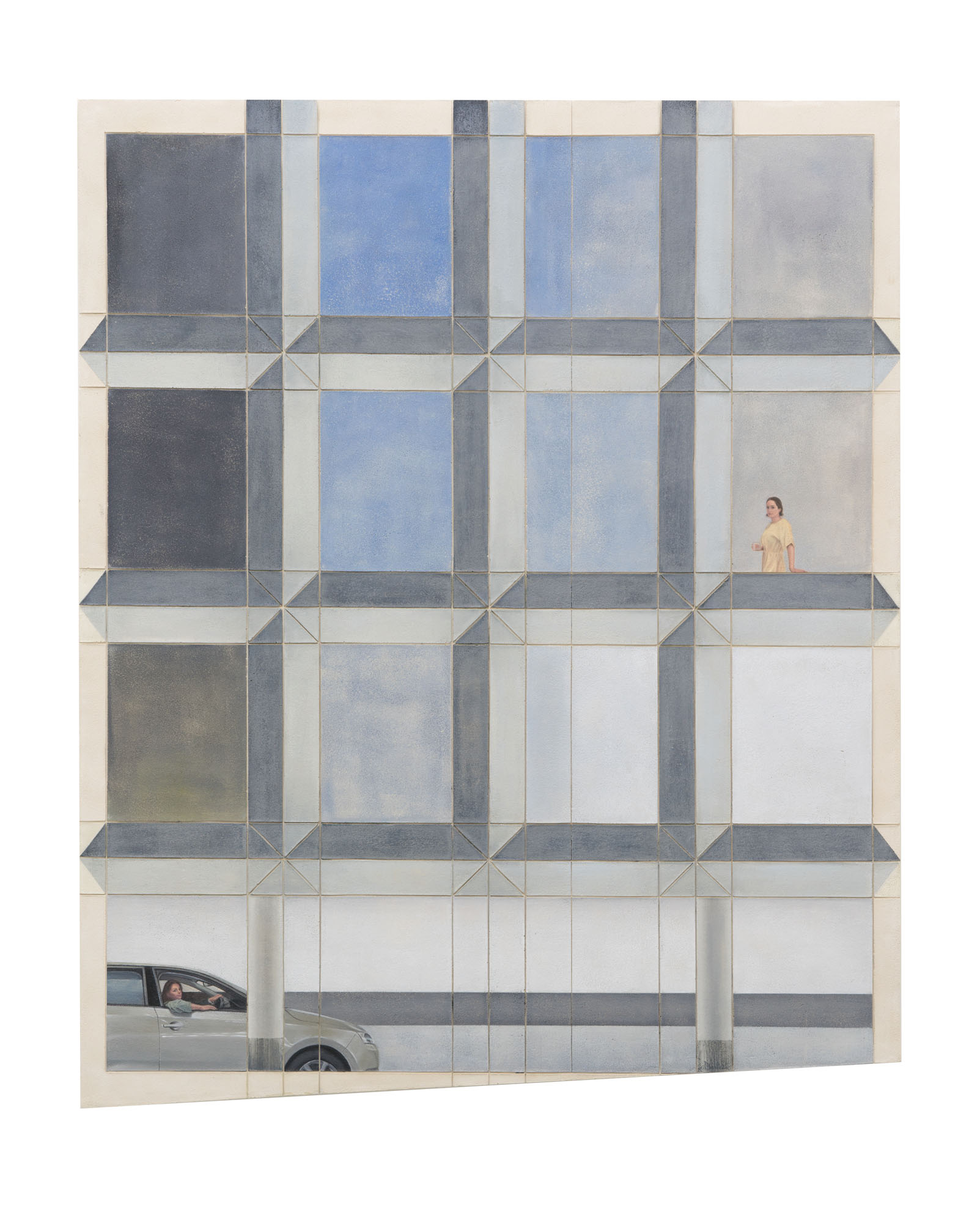

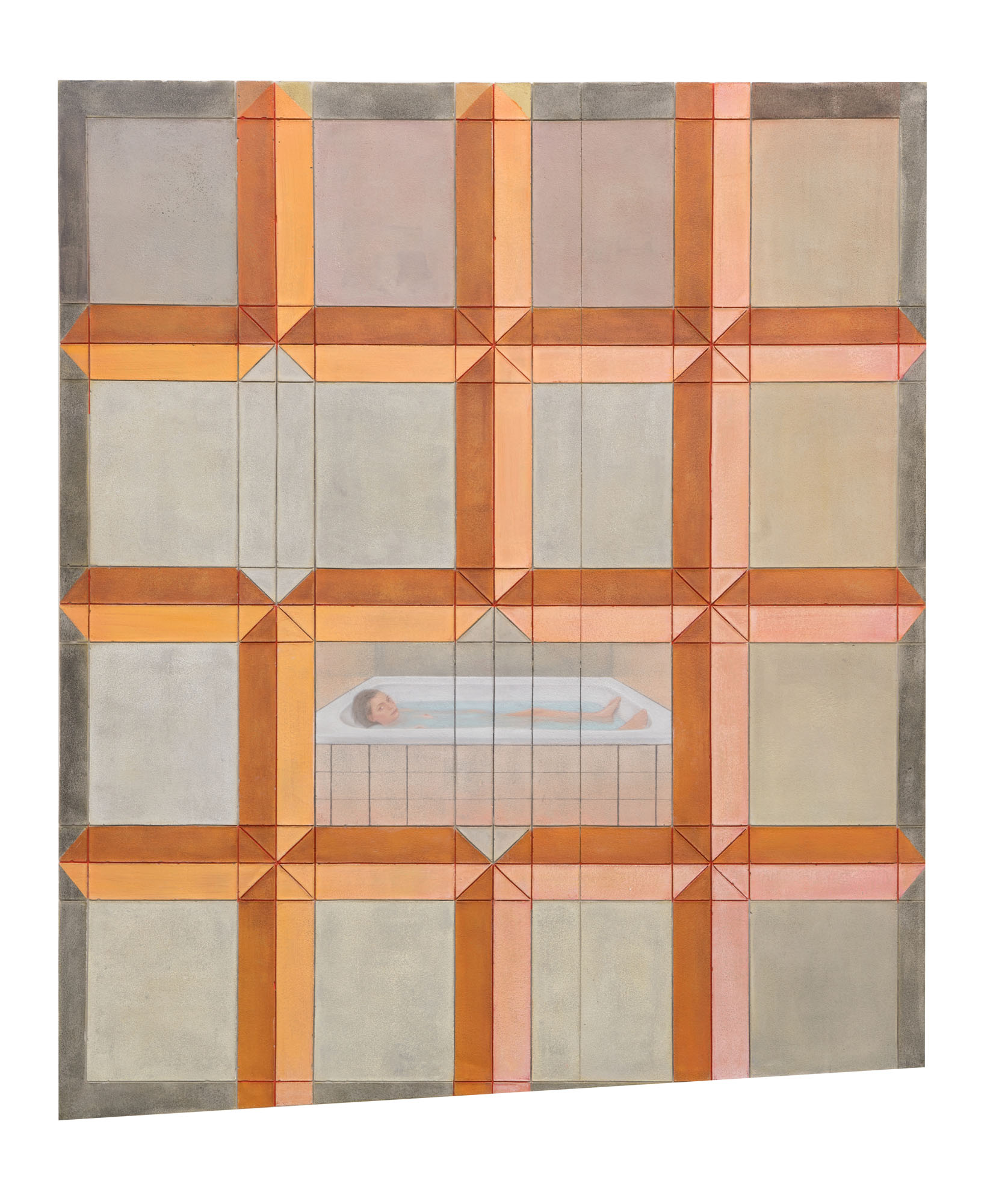

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'High Rise', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm

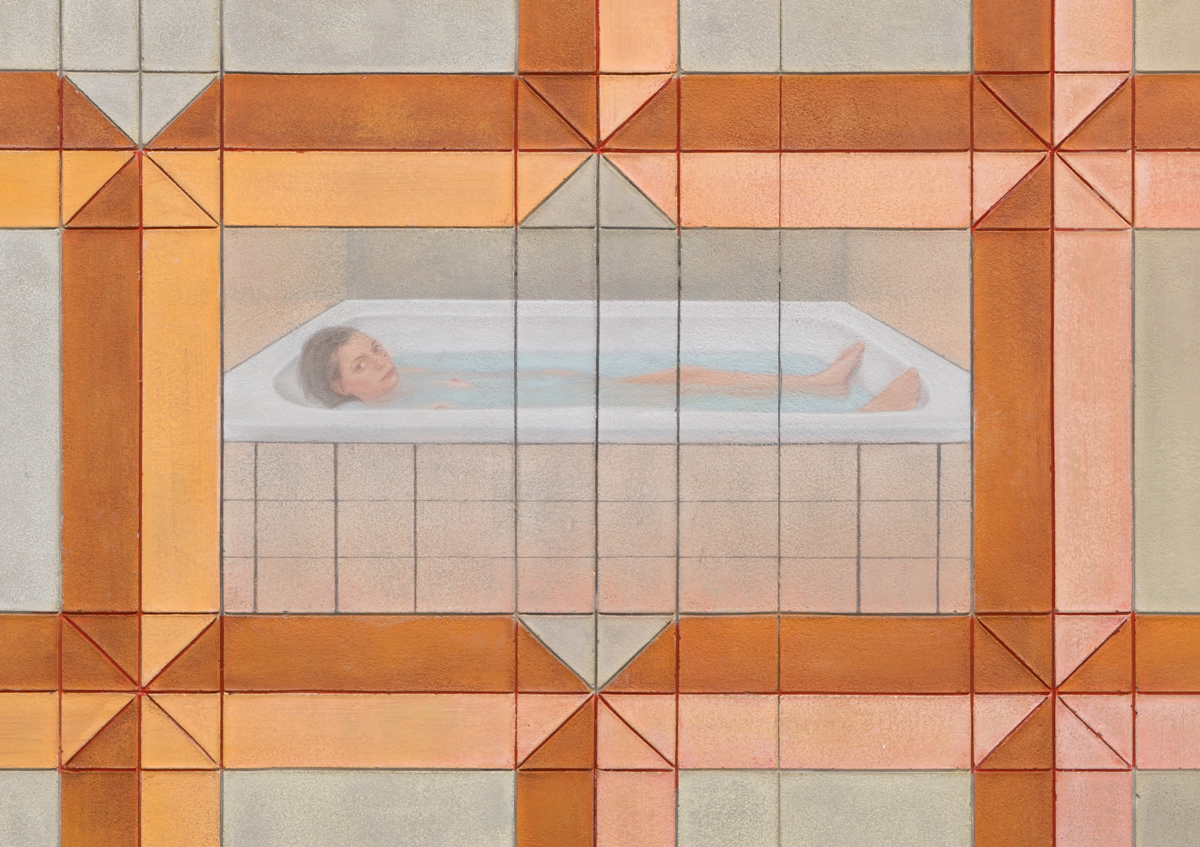

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'High Rise', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm (Detail)

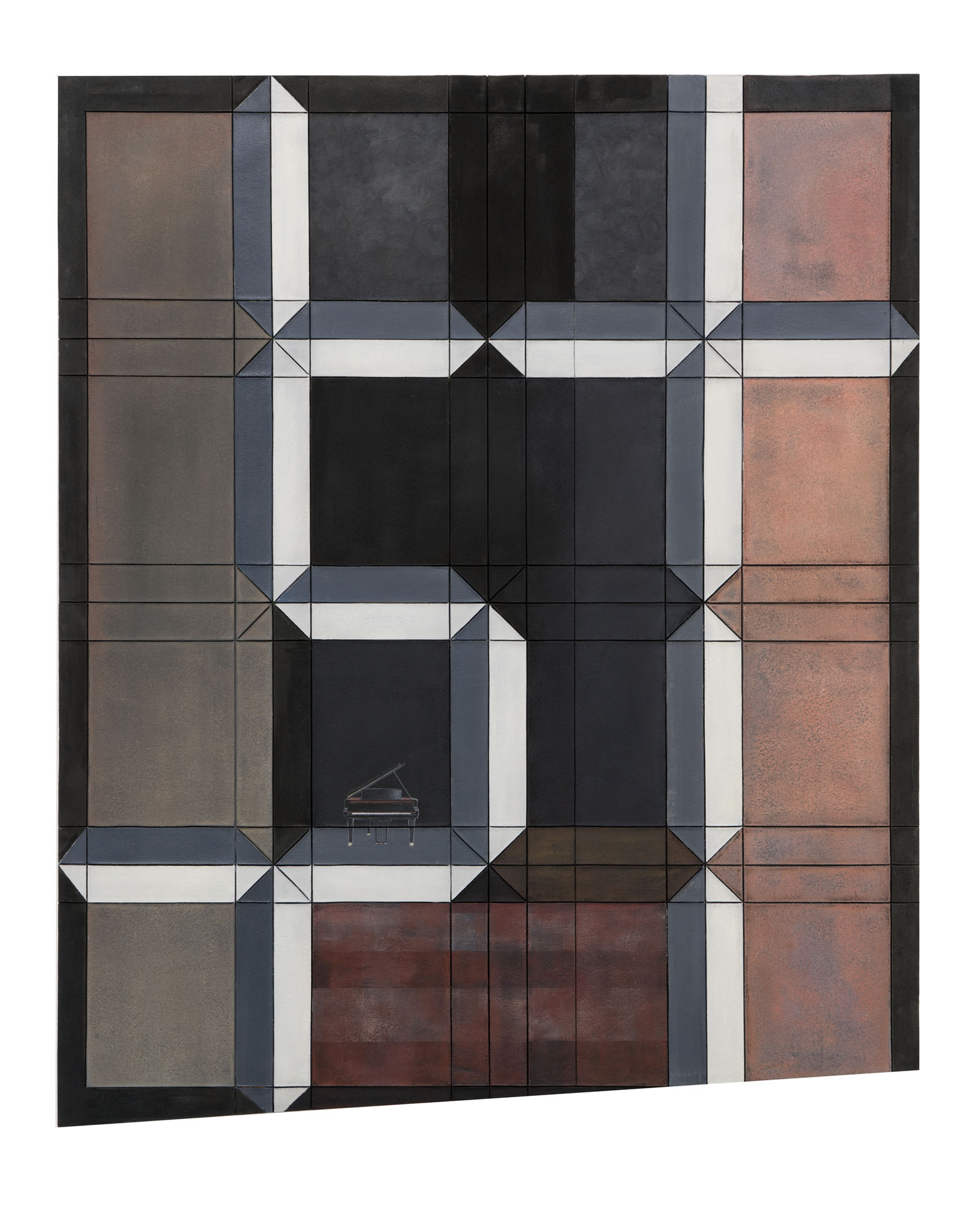

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'Grand Piano', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'Grand Piano', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm (Detail)

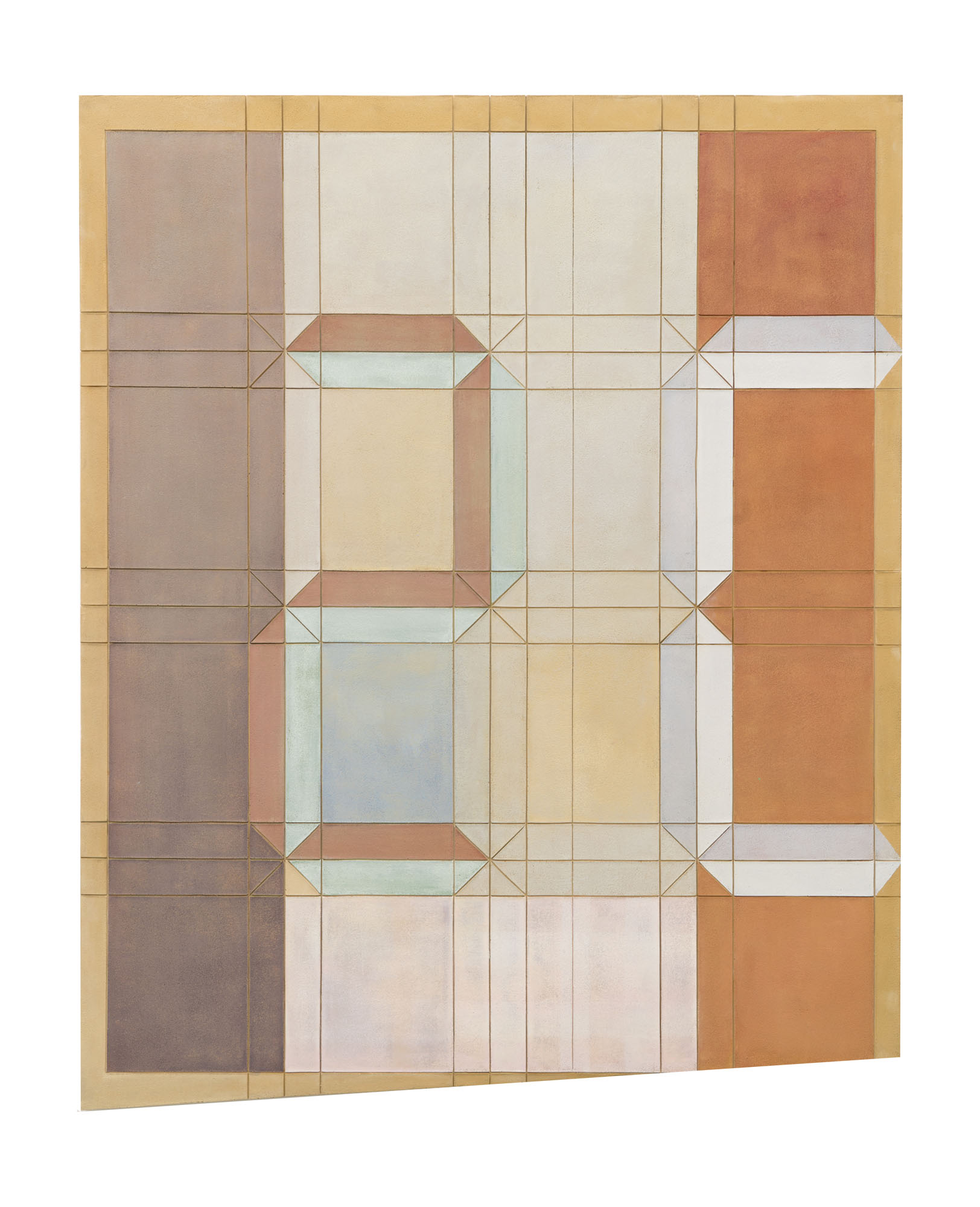

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'Interlude with Sunset', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm

Melanie Ebenhoch, 'Interlude with Sunset', 2017, Oil on Aqua-Resin, 110 × 90 cm (Detail)

The cinematographic, theatrical scenes of Toot Suite are depicted in a fresco-like sequence of six paintings. Their color palette suggests the cycle of a day — twilight, morning, noon, afternoon, dawn, night — the narrative, however, gives no evidence to how they are connected, there is no apparent linear logic of events, no actual clues of a storyline at all. Instead, the protagonists seem to be floating through ghostly environments. Clearly outlined and realistically rendered they attract our attention, yet they seem to be trapped behind a transparent veil. Despite their contemporary references and presence, they have fallen out of time.

Melanie Ebenhoch’s particular play with immersion and intimacy, fueled by trompe l’oeil details, and her technique negotiates the relationship between the female protagonists and the space of the viewer. Take, for instance, the architectural grids that prominently connect the six paintings, and are carved into the cast Aqua-Resin, forming frames or windows to sub-narrations of different tempo-spatial logics. Giotto, the alleged inventor of linear perspective, and his architectural settings and miniature storytelling, may come to mind. Ebenhoch’s paintings intensify claustrophobic qualities, as motifs are squeezed into them, such as with the scene of the nude in the bathtub, or, they may convey a feeling of too much space and solitude. The fact that, upon closer observation, some of the grids turn out to be the digital numbers 57, 25, 23, 20 of the doomsday clock — the measurement in time of how close the world is to a global catastrophe (momentarily at 23:57) — may be as much of a formal play as a reference to Iannis Xenakis on the sheet of music placed above the piano in Piano Bar – Keys don’t fit (2017).The Corbusier student translated the space of architectural planes into musical time of sheer, scintillating physicality — music, that the young brunette leaning over the sheet of music and piano, shows no interest in playing. Conspicuously, throughout the paintings, realism and narration continuously bounce back from their own mediality and the constructs of time and space.

The gaze that connects the relationship triangle of artist – painting – viewer, is without exception a female one: the protagonists are self-portraits of Ebenhoch — as a nude in the bath tube or casually driving a car — and portraits of the artist’s close friends, holding a drink or leaning out of the painting, like they might stumble into the space of the gallery at any moment. Are they bored, in reverse, or simply provocatively withstanding our gazes? The depicted womanhood speaks of vulnerable confidence, fragility, and strength. Toot Suite probes the possibilities and restraints of being a female artist, of female (self) representation and of inscribing oneself into an (art) history, made by man. Not without a humorous undertone: a sense of nostalgia, that emanates from the chosen color palette, is also evident in the cover of the exhibition announcement – an illustration of Live alone and like it, a guide for independent single woman on how to hold themselves apart from men, published by Vogue editor Marjorie Hillis in 1936. More than 80 years ago.

Franziska Sophie Wildförster, 2018