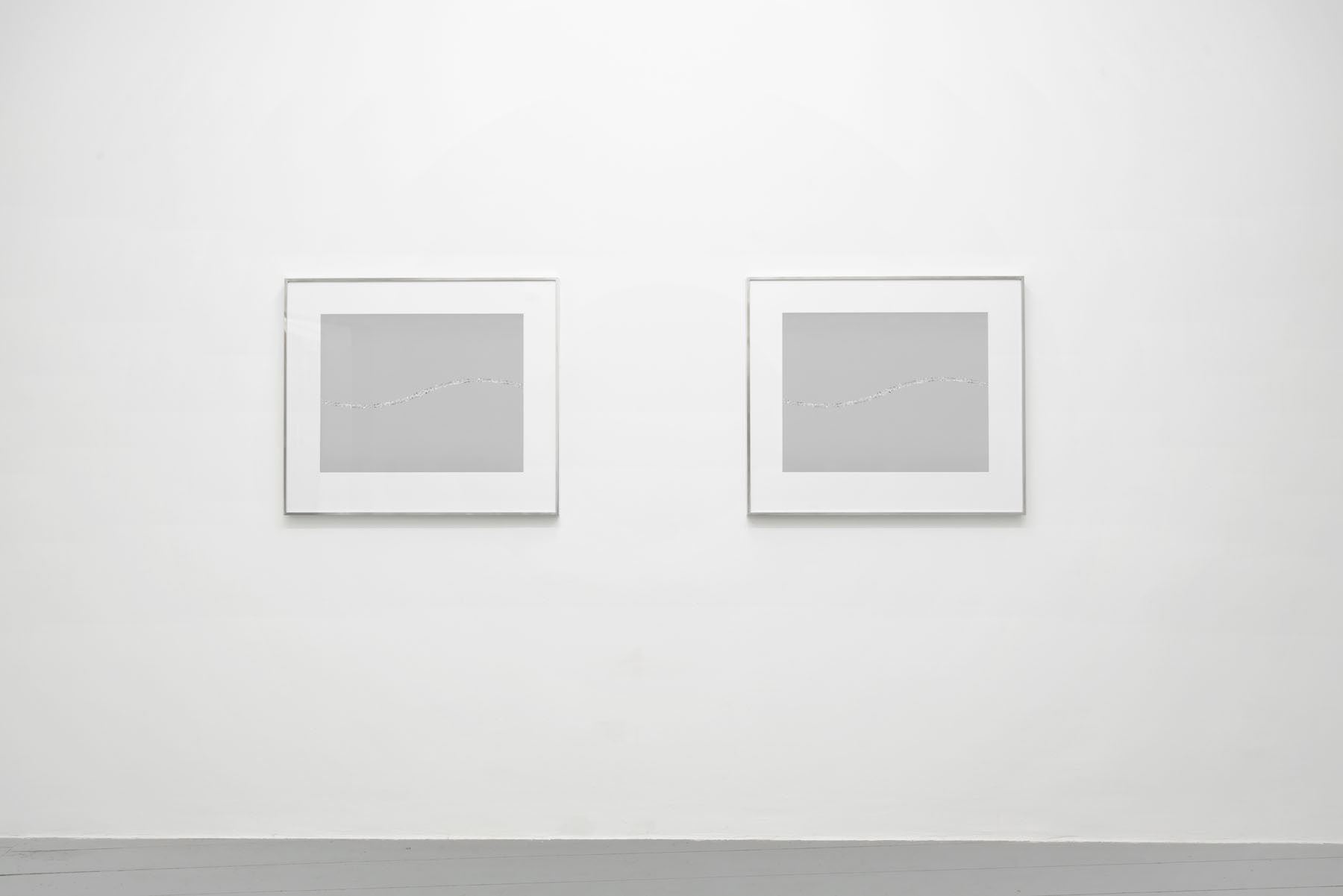

Oskar Schmidt, Installation view, Galerie Tobias Naehring 2018

Oskar Schmidt, Installation view, Galerie Tobias Naehring 2018

Oskar Schmidt, Installation view, Galerie Tobias Naehring 2018

Oskar Schmidt, ‘Hand (No.2)‘, 2017, C-print, each 104 × 125 cm

Oskar Schmidt, ‘Portrait (No.4)‘, 2017, C-print, 143 × 117 cm

Oskar Schmidt, ‘Water (No.3)‘, 2017, C-print, 104 × 125 cm

Oskar Schmidt, Installation view, Galerie Tobias Naehring 2018

Oskar Schmidt, Installation view, Galerie Tobias Naehring 2018

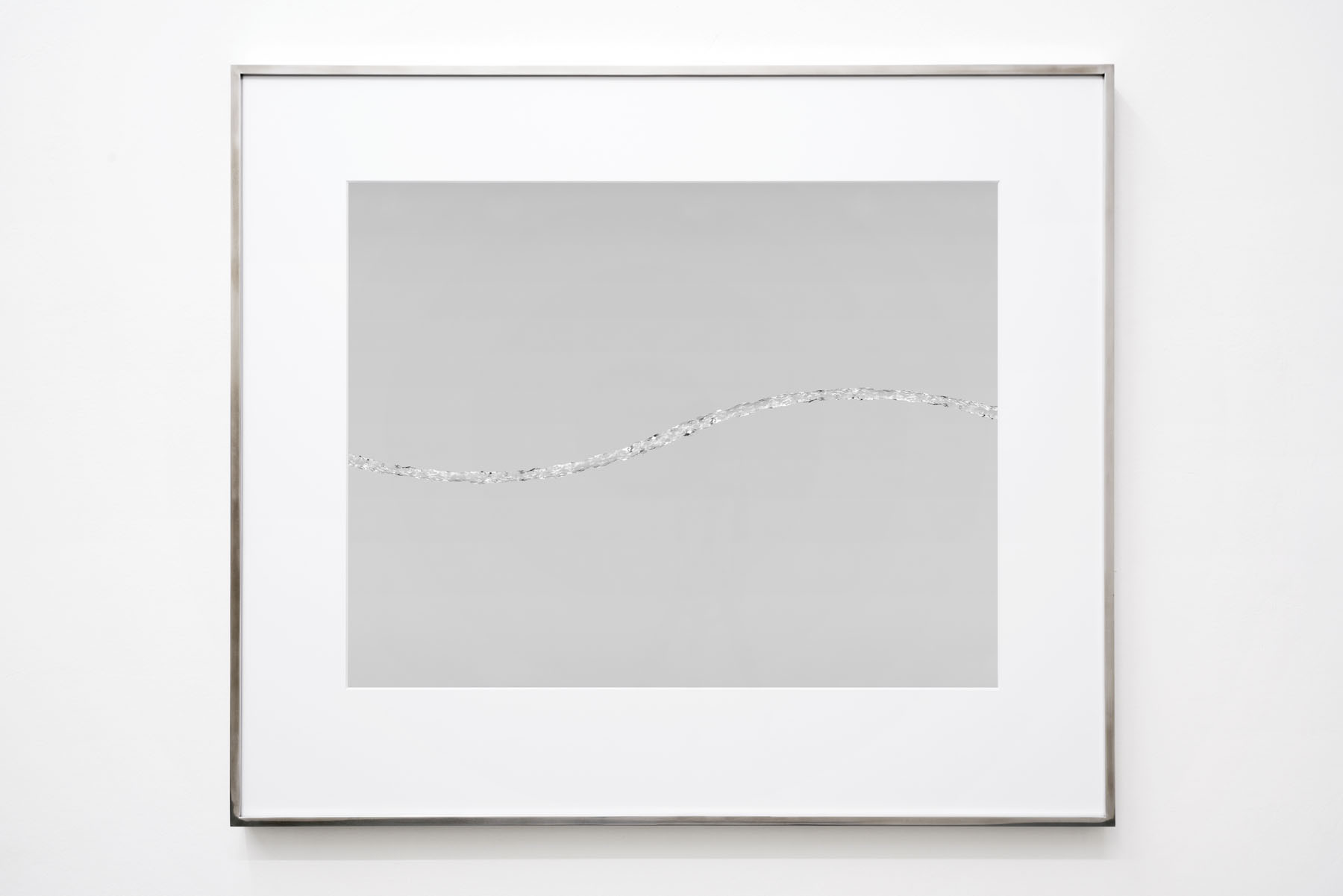

Oskar Schmidt, ‘Water (No.4)‘, 2018, Gelatin silver print, 51 × 64 cm

A single stream of water bisects two photographic works included in Oskar Schmidt’s first solo exhibition at Galerie Tobias Naehring, tracing identical lithe arcs with the gentleness of a sine-wave. Suspended improbably aloft in mid-air, the liquid flows without clear directionality, lacking gravitational coordinates. It jumps frames in one diptych, repeating itself across two photographs like a graceful stutter.

Liquidity suggests exchange, flexibility, and adaptability. To be liquid is to change state casually, to skip borders, to live free of friction, of footprint, of dead weight—to embody that which lacks body. Liquidity is the utopia of a dematerialized, option-rich world in practice. And yet, liquid is the most stubbornly corporeal of materials, too. (“What does water do for you?” suggests Google, piping in with a question that leads, as always, to another question. “Water Helps Maintain the Balance of Body Fluids,” it answers itself.)

The human body occupies two other works in this exhibition. A youthful face is seen in three-quarter profile, eyes redacted by a close cropping, floats against a corporate baby blue background. In another diptych, two identical hands reach towards each other across their respective frames, a sisyphean grasp at human communion. Hands, lips, and skin take on an anonymous, waxen, tantalizing sheen; Schmidt pauses the instant just before body becomes gestalt.

Each photograph is shot on a large format camera and subsequently digitally manipulated; in one case, the image even results in a silver gelatin print, bringing the analog and digital full circle. Schmidt stages his images in lived space and then treats them with the toolkit of a corporate techno-optimism in which everything can be made to feel simultaneously more, and less, real. This depends, of course, on your ability to suspend disbelief. It was the romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge who coined the term “suspension of disbelief,” and long before the days of photoshop. He reasoned that a modicum of „human interest and a semblance of truth“ could make an otherwise fictional scenario easily swallowed—could make you turn, in other words, a blind eye to dramaturgy. It is this staging that Schmidt returns to the fore.

Josephine Graf, 2018