Installation view: Thomas Rentmeister, ‘Wilk Star. Neue Arbeiten’, June 26 — September 4, 2021, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Installation view: Thomas Rentmeister, ‘Wilk Star. Neue Arbeiten’, June 26 — September 4, 2021, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Thomas Rentmeister, Untitled, 2021, Aluminum on canvas, 150 × 112 × 5 cm

Installation view: Thomas Rentmeister, ‘Wilk Star. Neue Arbeiten’, June 26 — September 4, 2021, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Installation view: Thomas Rentmeister, ‘Wilk Star. Neue Arbeiten’, June 26 — September 4, 2021, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Thomas Rentmeister, 'fifty-fifty Matratze', 2020, Aluminum on canvas, 27,5 × 14 × 2,5 cm

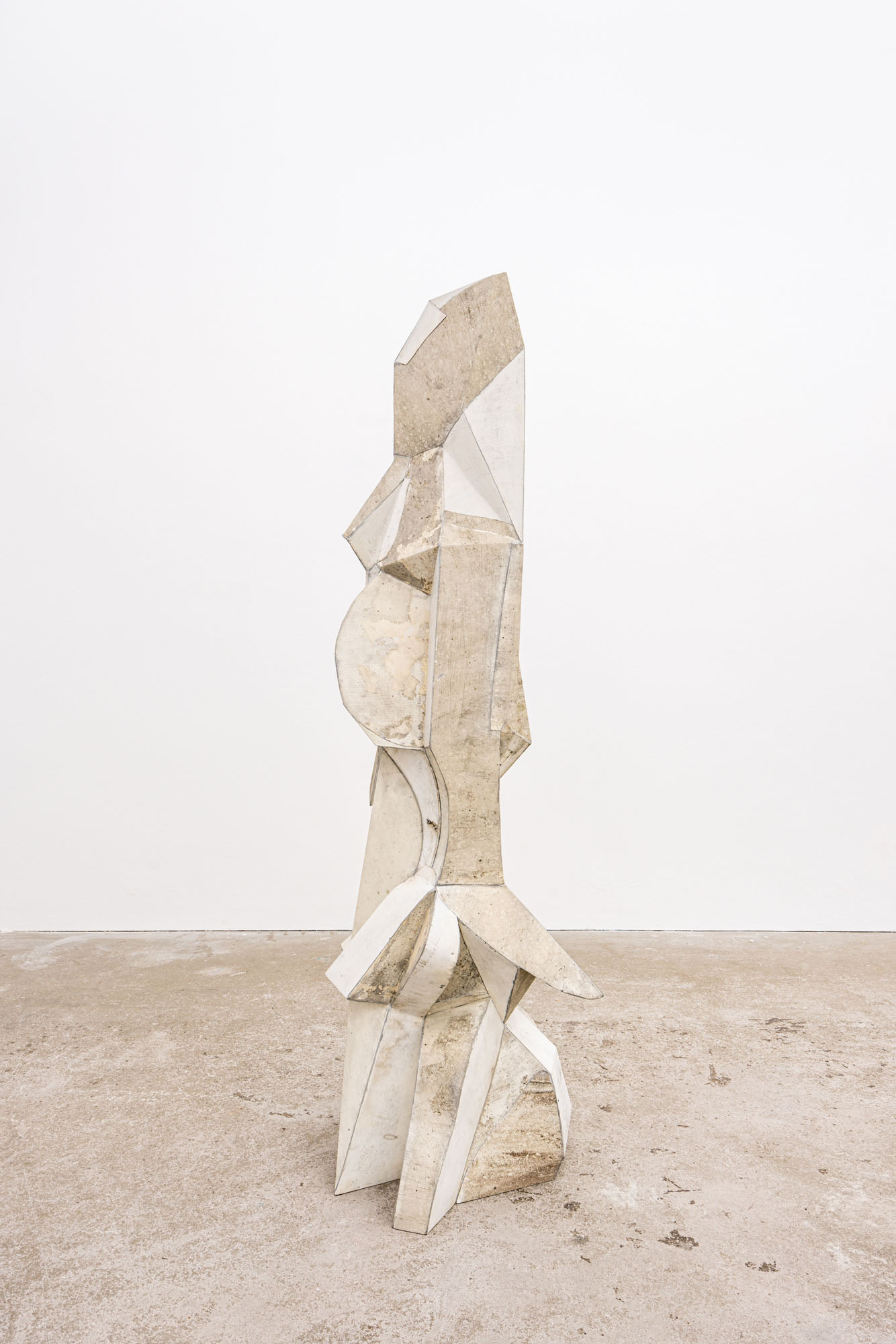

Thomas Rentmeister, 'Wilk Star', 2021, Aluminum, 214 × 68 × 65 cm

Installation view: Thomas Rentmeister, ‘Wilk Star. Neue Arbeiten’, June 26 — September 4, 2021, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

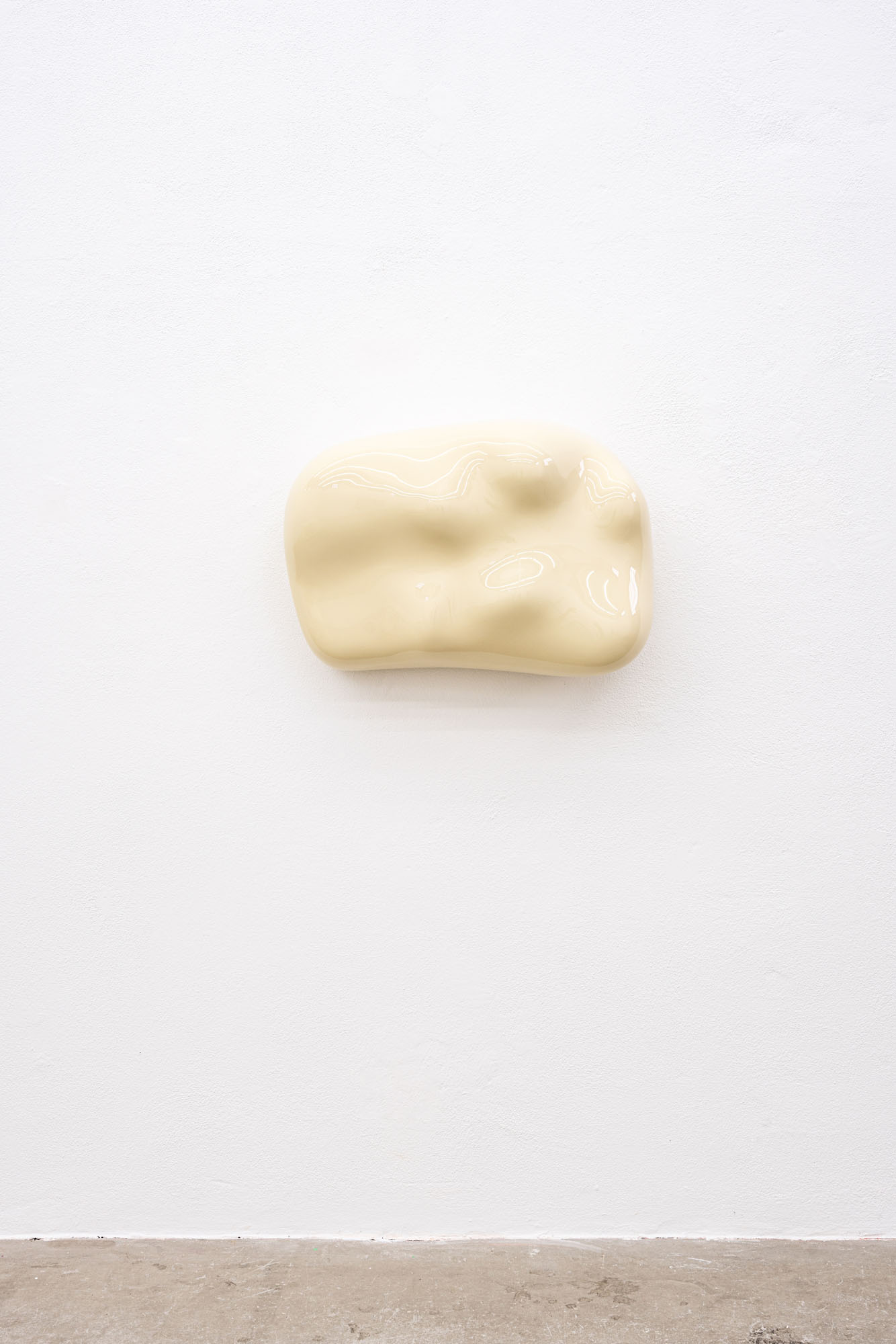

Thomas Rentmeister, Untitled, 2021, Polyester, 59 × 84 × 34 cm, Ed. 5

Thomas Rentmeister, 'IBC-Container', 2021, Steel, cotton, 115 × 150 × 120 cm

Thomas Rentmeister, '800', 1988, Reflective foil on aluminium, 120 × 160 × 10 cm

When art critics speak of nomadic life, they usually do so in a figurative sense. According to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, it involves a high degree of mobility and artistic freedom, the necessity of crossing borders, and an element of nonconformism in art. Or—in reference to Mieke Bal—the vagabonding between disciplines and media, geographical reference systems and historical epochs is described by nomadism’s „wandering concept“.

In the case of Thomas Rentmeister, however, it takes on a very concrete form. The artist detaches the scintillating metaphor of the nomadic from its discursive framework and links it to real materials, spaces, and experiences. It is no coincidence that his sculpture Wilk Star, composed of polygons, looks as if it has traveled through time, even all the way to the stars, and on its way has come into contact with Jacques Lipchitz’s angular Cubism, with Russian Constructivism, with Constantin Brancusi’s serial principle of the endless column, with John Chamberlain’s assemblages, with Claes Oldenburg’s Ghosts, and with New York Minimal Art. Indeed, as the title suggests, this sculpture has already experienced a first life and undergone the adventurous process of transformation. It was once a vessel which, because of its nomadic and sculptural qualities, but also its patina, deserved to be resurrected as a work of art. Ab ovo it was a caravan, built in 1964, tired of roaming around, which in the context of the exhibition „JaJa NeinNein Vielleicht“ in Munich’s Gasteig—stripped down to its shell by Thomas Rentmeister, filled with gravel stones and bearing the neon lettering „von wegen“—relates the tale of being stranded after a long journey. Through months of patient devotion, Thomas Rentmeister has now coaxed from this same shell the sculpture Wilk Star, which—although made of aluminum—gives the appearance of a rendered collage of materials from the remnants of 20th century sculpture. On its way into the digital twilight dreaming of dematerialization, it has become a lightweight, albeit a rough-edged one.

The other remnants of the caravan also lead lives of their own, permeated by fractures. In the mosaic Outer Shell, the fragments come together to form an indefinable topographical map that owes its porous interface and reduced color to the material itself. In this exhibition, the nomadic is thus not connected with the imaginative power of the mythical figure of the restlessly wandering artist, but instead with the concrete objects that surround him. Be it the cuboid container, devised for the global chemical trade and now the source material for the sculpture IBC-Container, which leans towards the anthropomorphic on account of its interior’s fuzzy structure. Or fifty-fifty-Matratze, made of cast white marble and converted into a convenient format, which—quite in contrast to Robert Rauschenberg’s legendary Bed sullied with bodily fluids—neither permits the thought of intimacy, nor is it capable of conforming to the bodies of repose-seeking global players. Thus, the question of where the journey is headed in art, in society, in climate policy, cannot be delegated to the ideal of a world-experienced nomadic artist. It is rather up to the viewers to seek answers and reflect on all this, mirrored in the shiny surface of the cream-white polyester sculpture Untitled.

Annette Tietenberg, 2021