Felix Schramm, 'Multilayer #334B', 2020, Plasterboard, paint, photo wallpaper, 310 × 125 × 21 cm

Installation view: Felix Schramm 'The Verge' , February 19 — April 23, 2022, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Installation view: Felix Schramm 'The Verge' , February 19 — April 23, 2022, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Felix Schramm, 'Multilayer #426', 2022, Plasterboard, paint, inkjet print, 170 × 130 × 27 cm

Installation view: Felix Schramm 'The Verge' , February 19 — April 23, 2022, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

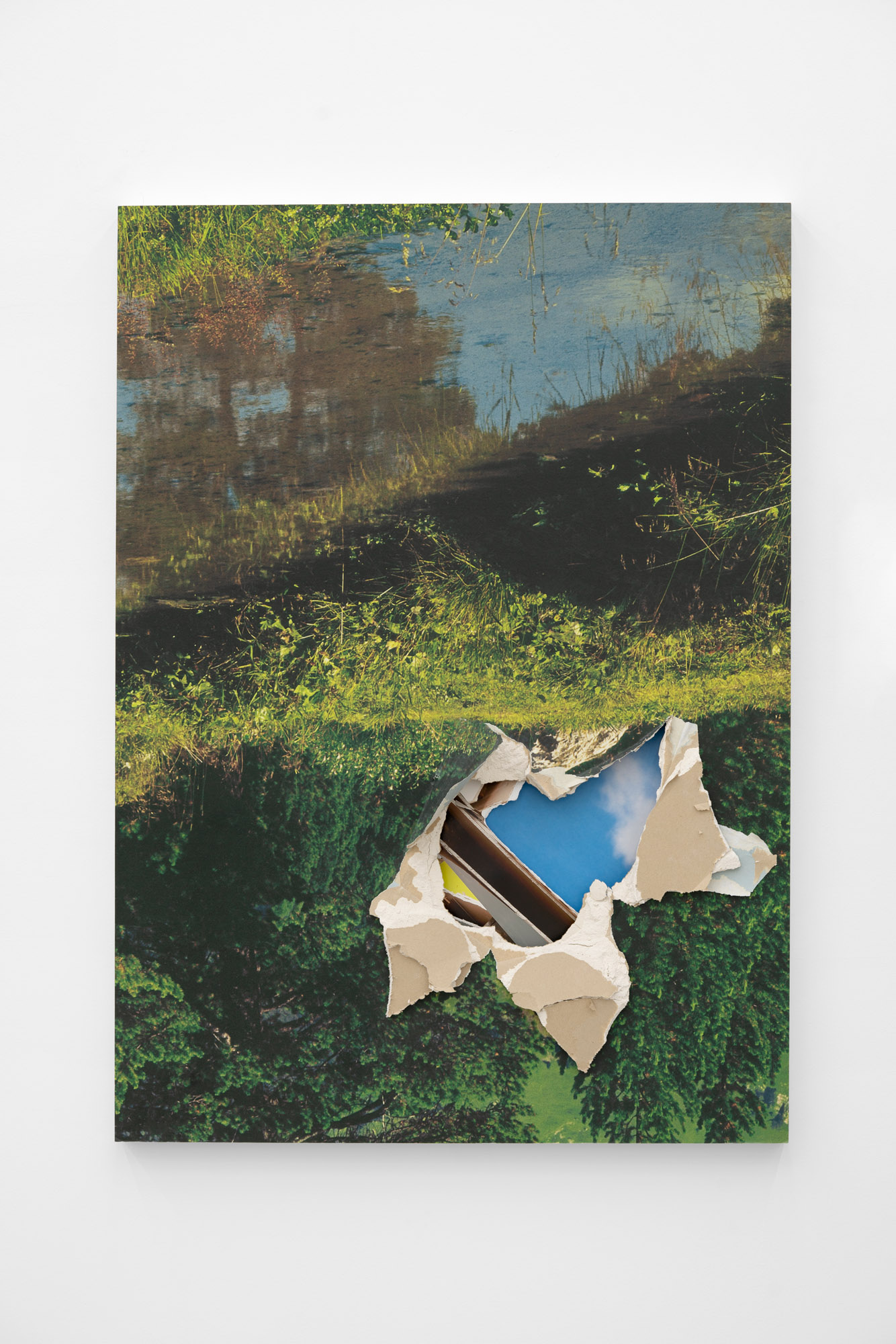

Felix Schramm, 'Multilayer #434', 2020, Plasterboard, paint, photo wallpaper, 136 × 96,5 × 19 cm

Installation view: Felix Schramm 'The Verge' , February 19 — April 23, 2022, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Installation view: Felix Schramm 'The Verge' , February 19 — April 23, 2022, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Felix Schramm, 'Multilayer #425', 2022, Plasterboard, paint, inkjet print, 170 × 130 × 23,5 cm

Felix Schramm, 'Multilayer #425', 2022, Plasterboard, paint, inkjet print, 170 × 130 × 23,5 cm

Installation view: Felix Schramm 'The Verge' , February 19 — April 23, 2022, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Installation view: Felix Schramm 'The Verge' , February 19 — April 23, 2022, Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig

Felix Schramm, 'Dark Site #47', 2021, Dust, silver leaf, acrylic glass, 200 × 150 × 5 cm

Felix Schramm, 'Dark site #34', 2020, Dust, silver leaf, acrylic glass, 80 × 60 × 5 cm

(English version below)

„Es gibt ein Bedürfnis nach dem Ganzen. Allerdings glaube ich, dass das Ganze, die Idee der Ganzheit, heute unerreichbar geworden ist.“(1)

In der Antike sahen sich die Künste grundsätzlich der Vollkommenheit verpflichtet, die als ästhetische Kategorie bis in die Frühe Neuzeit alles Unvollendete oder Unvollständige wertlos machte. So postulierte Thomas von Aquin in der Mitte des 13. Jahrhunderts nachdrücklich: „Die Dinge nämlich, die verstümmelt sind, sind schon deshalb hässlich.“

Erst mit Anbruch des 18. Jahrhunderts wurde das Fragment als eigenständige Gattungsform eingeführt, um sich nun im Kontrast zu der als unnatürlich wahrgenommenen Ganzheitsästhetik einer „unverfälschten Emotionalität“ anzunähern. In der Bildenden Kunst war es damals vor allem Johann Joachim Winckelmann, der mit seiner richtungsweisenden Beschreibung des Torso vom Belvedere das fragmentarische Motiv zum Ideal erhob, womit er letztlich den Weg für sämtliche Abstraktionstendenzen ebnete. Mit den beiden Weltkriegen ging in Deutschland zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts der Glaube an eine Gesamtheit gänzlich verloren, was nicht nur Theodor W. Adornos Aussage „Das Ganze ist das Unwahre“ unterstreicht. Als praktische Konsequenz daraus, werteten beinahe alle Avantgardebewegungen der Moderne die Bedeutung des Fragmentarischen auf, indem sie beispielsweise vermehrt mit Collage- und Montagetechniken experimentierten.

Die Galerie Tobias Naehring freut sich nun ab dem 19. Februar 2022 unter dem Titel „The Verge“ eine Einzelausstellung des Düsseldorfer Bildhauers und Fotografen Felix Schramm (*1970 in Hamburg) zeigen zu können, dessen vielgestaltiges Œuvre überzeugend bekräftigt, dass sich jedes vermeintlich „fertige“ Kunstwerk in einem unendlichen Kontext von Produktion und Rezeption befindet. Durch die Entwicklung komplexer Fragmentkonstruktionen – einer bewussten Antithese von Zerstörung und Kreation – lenkt der Künstler den Betrachtenden geschickt in Momente der Irritation und des Hinterfragens. Seine Arbeiten interagieren offen mit Raum und Zeit, negieren die existentielle Abhängigkeit von einer Vollendung und werden so zur Verbildlichung einer Generation ununterbrochener Schaffensprozesse.

Text von Anna Goltz

„There is a need for the whole. However, I believe that the whole, the idea of wholeness, has become unattainable today.“(1)

In antiquity, the arts were fundamentally committed to perfection, which, as an aesthetic category, rendered everything unfinished or incomplete worthless until the early modern period. Thus, in the mid-13th century, Thomas Aquinas emphatically postulated: „Those things, namely, which are mutilated are for this reason alone ugly.“

It was not until the dawn of the 18th century that the fragment was introduced as an independent genre form in order to approach an „unadulterated emotionality“ in contrast to the aesthetic of wholeness, which was perceived as unnatural. In the visual arts at that time, it was above all Johann Joachim Winckelmann who elevated the fragmentary motif to the ideal with his trend-setting description of the torso from the Belvedere, thus ultimately paving the way for all tendencies towards abstraction.With the two world wars, the belief in a totality was completely lost in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century, which is not only underlined by Theodor W. Adorno’s statement „The whole is the untrue“. As a practical consequence of this, almost all avant-garde movements of modernism valorized the significance of the fragmentary, for example by increasingly experimenting with collage and montage techniques.

Galerie Tobias Naehring is now pleased to present a solo exhibition of the Düsseldorf-based sculptor and photographer Felix Schramm (*1970 in Hamburg), whose multifaceted œuvre convincingly affirms that every supposedly „finished“ work of art is situated in an infinite context of production and reception. By developing complex constructions of fragments – a deliberate antithesis of destruction and creation – the artist skillfully directs the viewer into moments of irritation and questioning. His works interact openly with space and time, negating existential dependence on a completion and thus becoming the visualization of a generation of uninterrupted creative processes.

text by Anna Goltz

(1) Felix Schramm im Gespräch mit Stephan Berg, in: Ausst. Kat.: Felix Schramm, Intersection, Nürnberg 2012. / Felix Schramm in conversation with Stephan Berg, in: Felix Schramm, Intersection, Nuremberg 2012.